Sidequests And Loose Ends

by Jan Kelemen

Once more I continued to work on the gltfviewer demo for my game engine jan-kelemen/niku.

There were a couple of rendering features that weren’t yet covered and some quality of life improvements.

Diff from the state shown in previous post.

As before all sample assets shown are from KhronosGroup/glTF-Sample-Assets.

Runtime shader compilation

Vulkan uses SPIR-V for shaders. SPIR-V is an binary representation of the shader code, it’s not meant to be written by humans directly. This choice allows among other things to write the shaders in any language that can compile down to SPIR-V.

I chose to write my shaders in GLSL.

To compile GLSL code to SPIR-V one can use glslc or glslangValidator command line applications included in the Vulkan SDK.

This approach is ok as long as there is no need to support different shader variants, in that case all of the variants would have to be compiled upfront and deployed. For example, my PBR shader needs an additional output attachment when rendering transparent geometry, while the other 90% of the shader code is identical.

#ifndef OIT

layout(location = 0) out vec4 outColor;

#else

layout(location = 0) out vec4 outAcc;

layout(location = 1) out float outReveal;

#endif

Instead of precompiling everything upfront to SPIR-V, the shaders can be compiled at application startup with glslang.

This is the same reference backend used by the glslc and glslangValidator compilers.

I created a small abstraction around it, vkglsl::shader_set_t, that’s intented to be used as a container for all shaders that will be a part of a graphics or a compute pipeline.

vkglsl::shader_set_t shader_set{};

auto vertex_shader{add_shader_module_from_path(shader_set,

backend_->device(),

VK_SHADER_STAGE_VERTEX_BIT,

"pbr.vert")};

auto fragment_shader{add_shader_module_from_path(shader_set,

backend_->device(),

VK_SHADER_STAGE_FRAGMENT_BIT,

"pbr.frag",

std::array{"OIT"sv})}; // Preprocessor constant

Currently, it supports adding shaders either as a GLSL source code or directly as a SPIR-V binary.

For the shaders that are compiled, preprocessor constants and additional include directories for #include statements can be added.

Descriptor set layout reflection

One of the more verbose parts of the Vulkan API is descriptor sets. They are a way of describing resources used by the shader like buffers, images, samplers and similar. A descriptor set requires a descriptor set layout which is a structure declaring individual bindings contained in the descriptor set.

[[nodiscard]] VkDescriptorSetLayout create_descriptor_set_layout(

vkrndr::device_t const& device)

{

VkDescriptorSetLayoutBinding combined_sampler_binding{};

combined_sampler_binding.binding = 0;

combined_sampler_binding.descriptorType =

VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_COMBINED_IMAGE_SAMPLER;

combined_sampler_binding.descriptorCount = 1;

combined_sampler_binding.stageFlags = VK_SHADER_STAGE_FRAGMENT_BIT;

return vkrndr::create_descriptor_set_layout(device,

std::span{&combined_sampler_binding, 1});

}

The code snippet above creates a descriptor set layout with one binding for a combined image sampler.

Luckily most of this information can also be extracted by reflecting on the contents of the SPIR-V shader binaries with libraries like SPIRV-Cross or SPIRV-Reflect. My understanding is that for the purposes of reflection, the main difference between these two is that SPIRV-Reflect does not support specialization constants. SPIRV-Cross also supports cross compilation from SPIR-V back to human readable code in GLSL, HLSL and other shader languages, so it’s a bigger library in general.

I chose to go with SPIRV-Cross anyway since most of the other features can be disabled during the compilation of the library.

With the SPIR-V binaries for the whole shader set now loaded, the individual VkDescriptorSetLayoutBinding structures can be assembled from the reflected data.

auto const declare_resources =

[&](spirv_cross::SmallVector<spirv_cross::Resource> const& resources,

VkDescriptorType const type)

{

for (spirv_cross::Resource const& resource :

std::views::filter(resources, filter_descriptor_set))

{

uint32_t const binding{compiler.get_decoration(resource.id,

spv::DecorationBinding)};

auto& bind_point{binding_for(binding)};

bind_point.descriptorType = type;

bind_point.descriptorCount = 1;

bind_point.stageFlags |= to_vulkan(lang);

}

};

spirv_cross::ShaderResources const resources{

compiler.get_shader_resources()};

declare_resources(resources.sampled_images,

VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_COMBINED_IMAGE_SAMPLER);

This functionality is also a part of the previously mentioned vkglsl::shader_set_t abstraction and can be used most of the time.

One piece of the information that can’t be generated with reflection is the size of the arrays as this isn’t available in the shader code.

layout(set = 0, binding = 0) uniform sampler2D backbuffer[];

layout(rgba16f, set = 0, binding = 1) uniform image2D image[];

Command buffer scopes and object names

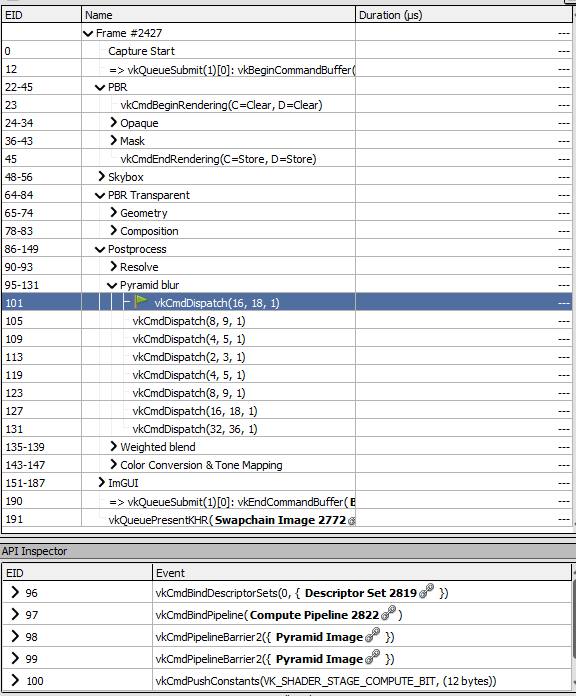

This one is mostly for my quality of life. The rendering code has become complex enough that it’s not trivial to figure out what the individual calls on the GPU correspond to.

I’ve extended my support for VK_EXT_debug_utils with command buffer scopes and object names.

The command buffer scopes are managed by a trivial RAII type that opens or closes a scope in the constructor or destructor respectively.

[[maybe_unused]] vkrndr::command_buffer_scope_t const

postprocess_cb_scope{command_buffer, "Postprocess"};

...

[[maybe_unused]] vkrndr::command_buffer_scope_t const cb_scope{

command_buffer,

"Pyramid blur"};

Nesting of the scopes is handled automatically by the extension/debugger.

Command buffer scopes group the draw calls under a tree structure, but it does not answer which resources the command is working on.

In RenderDoc they would be named something like Image 251, Compute Pipeline 2822.

To get something more semantically meaningful vkSetDebugUtilsObjectNameEXT needs to be used to set the object name.

I’ve wrapped this to a object_name function, which delegates to the extension functions if they are loaded.

object_name(backend_->device(), pyramid_image_, "Pyramid Image");

This gives a much nicer debugging experience as seen below. I named only the most important objects so some of them are still using the generated names.

Bloom

Bloom is an effect visible around bright objects in the scene where the light bleeds around the object. In theory, it sounds simple, apply the blur effect to bright parts of the scene and mix it with the original image. In practice, it took three tries to get it right.

The intro video shows the bloom effect on timestamps 0:00 and 0:36.

For this, I’ve also implemented the glTF extension KHR_materials_emissive_strength, so that different emissive values can be compared side by side.

I implemented bloom as a postprocessing step which executes after the scene has been rendered. The first step is to filter out the bright parts of the image, which can be done using the luminance values of individual fragments.

Next step is to blur this filtered image, for this we generate a couple of lower resolution (downsampled) images. Afterward these images are additively combined (upsampled) together back to the original resolution, leading to the blured effect.

Finally the blurred image is combined with the original to give the bloom effect. The blurring step is visualized on timestamp 0:25 in the video.

A couple of notes on my experience from implementing this:

- Applying a Karis average to the prefiltering step reduces very bright pixels from pulsating when the camera moves, Brian Karis - Tone Mapping

- If possible do the prefiltering on a multisampled image for the same reason

- Upsampling lower resolution textures has to be done with a weight function applied to lower resolution images

- It’s best to keep the bloom factor to a low number around 0.15 to avoid bloom disasters

The video at timestamp 0:36 shows what the effect looks like without the weight function in the upsampling.

Lower resolution images produce a blocky result which is also too bright.

I choose to combine the lower resolution images with a 1/2^n distribution, where n is the upsampling step giving the most importance to the higher resolution images.

Order Independent Transparency

Last time I mentioned that I enabled lossless optimizations on model geometry. I optimized a bit too much, one of these optimizations was to optimize for overdraw which affected the models with transparent geometry in a bad way.

Hello to the sidequest of implementing Weighted-Blended OIT.

The basic idea is to accumulate the colors of the transparent geometry based on the weight factor that depends on the depth of the fragment being rendered.

The intro video demonstrates the results of this technique at timestamp 0:55.

Weighted-Blended OIT is an approximation but it requires a single geometry pass so it’s a good compromise over the alternatives like depth peeling. The other alternative would be not to optimize transparent geometry at all, although this solution would be only temporary and related to a specific model.

Other news

All of the tooling I use has started to support Clang 19. Therefore niku and my cpp-starter-template have been ported to the new Clang version. Took the opportunity to update all other dependencies to their latest versions too, thankfully, no issues popped up in this process.

The best news about this is that std::expected can now be used with all three of the big compilers!

Up until now, I avoided the topic of error handling a bit. I was expecting this change and didn’t want to get too many usages of other alternative error handling mechanisms into the code. Exceptions mostly seem like a bad idea to use with GPU related code. With that in mind, I’ll have to do some work on this in the near future.

Final words

I consider the gltfviewer demo now mostly done, there is an infinite amount of work remaining.

One could expand it with animations, instancing, shadows, a more precise PBR model or one of many glTF extensions.

I plan to do these on a need by need basis. There is some other game-enginish stuff I want to do next.

Advent of Code is coming up, so good luck to everyone.

For any questions or corrections to this post, leave a comment in discussion thread on GitHub or any other place where you see this.

Previous posts in the series:

- Rendering Physically Based Bugs

- Preparing For Physically Based Rendering

- I See Spheres Now

- Rendering Medvednica From a Heightmap

- It Goes In The Square Hole

- Chess engine visualization

- Remaking World 1-1 with Vulkan, mostly