Abusing GPUs

by Jan Kelemen

I figured out we no longer have to do software rendering, the Greed Processing Units are capable of doing graphics. So I continued working on my game engine jan-kelemen/niku.

With the exception of toji/optimized-sponza asset, all other assets are from KhronosGroup/glTF-Sample-Assets.

Compressed texture formats

According to the profiling results of the gltfviewer demo, rendering is bottlenecked by the sampling of texture images.

I’ve known about this for quite some time already, though I think I can’t do much about it, since the shader cannot invent pixel values out of thin air.

The GPUs do support compressed textures, some tradeoffs that can be done. The first part of the intro video shows comparisons of assets using regular textures and variants of the same assets using compressed textures.

If you’ve read the previous link, you are now familiar with the inner workings of block compression algorithms, so I’ll skip that :)

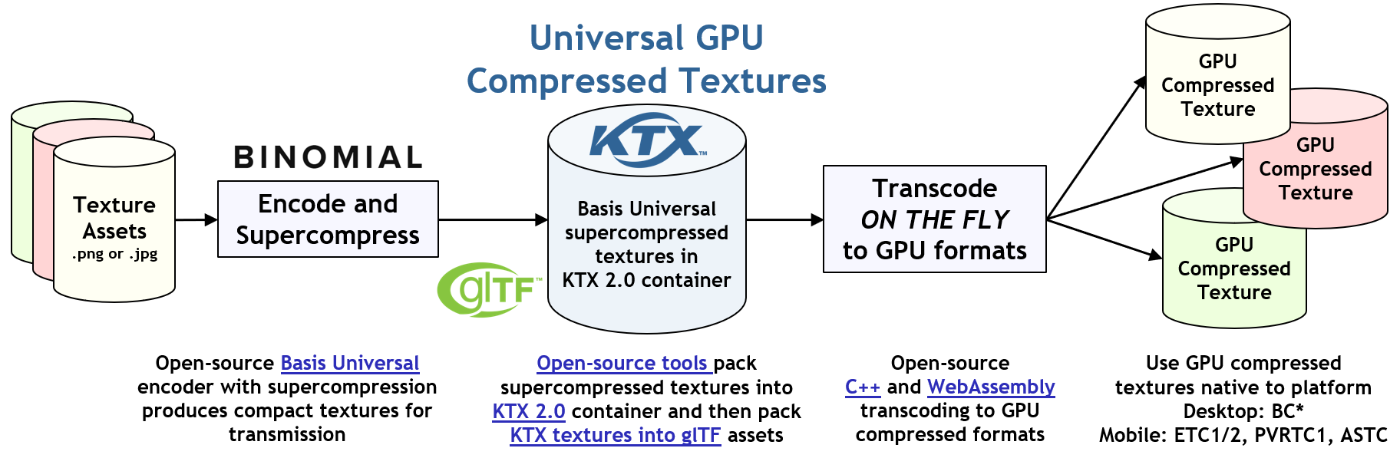

Different devices support a different set of compression algorithms, repackaging the same images with every compression schema isn’t a great solution. Basis Universal serves as an intermediate encoder for the image data.

Once we figure out which texture formats are supported by the device the application is running on, the data is transcoded into one of the supported formats. Aside from the file size, the benefit of using the basis encoding as an intermediate over regular JPG or PNG files is that it can be quickly transcoded into the compressed format. Compressing raw image data on the fly would be impractical. Time required for compression is higher than the transcoding time.

While I didn’t do memory measurements, I’m still missing proper memory tracking in the engine, KTX Artist Guide shows the memory usage for a stained glass lamp model that’s also showcased in the video.

Which brings me to Khronos Texture Format (KTX).

glTF doesn’t natively support Basis Universal images. They need to be packaged in KTX files, as defined by the KHR_texture_basisu extension.

A nice thing about KTX is that the file format supports storing mipmaps and other data required for loading the image as a texture.

I’ve decided to use the KTX parser that is included in the Basis Universal library, instead of the official KhronosGroup/KTX-Software. I didn’t like the idea of adding yet another library to the third party dependencies.

There are some visual differences between using the compressed textures vs the regular ones. The tradeoff does look acceptable considering the other benefits. While the performance benefit is not as much as I’ve hoped for, I did profile the rendering again. According to NVIDIA Nsight, VRAM usage is lower with optimized asset variants, so it is a step in the right direction.

My attempts to support these compressed textures resulted in a cool looking bug at one point, shown in the intro video at timestamp 3:04.

Programmable vertex pulling

In the previous post, I mentioned that I’ll look into programmable vertex pulling (PVP).

Instead of using vertex buffers, the gltfviewer demo is now loading vertices from the storage buffers.

layout(buffer_reference, buffer_reference_align = 64) readonly buffer VertexBuffer

{

PackedVertex v[];

};

Vertex unpackVertex(PackedVertex vtx);

layout(push_constant) uniform PushConsts

{

VertexBuffer vertices;

} pc;

void main()

{

const Vertex vert = unpackVertex(pc.vertices.v[gl_VertexIndex]);

The data that was previously packed in the regular vertex buffer is now in VertexBuffer,

I’ve changed it a bit to be tightly packed so it fits better within the power-of-2 alignment requirements.

The address to the storage buffer containing packed vertices is passed using buffer device addresses. While the rest of the world is getting scared of pointers, GPU programming is a sacred land where sending pointers to memory addresses is normal.

Switching to PVP also allows us to skip defining vertex attributes and binding descriptions in the CPU code and graphics pipeline layouts.

consteval auto binding_description()

{

constexpr std::array descriptions{

VkVertexInputBindingDescription{.binding = 0,

.stride = sizeof(glm::vec3),

.inputRate = VK_VERTEX_INPUT_RATE_VERTEX},

};

return descriptions;

}

consteval auto attribute_descriptions()

{

constexpr std::array descriptions{

VkVertexInputAttributeDescription{.location = 0,

.binding = 0,

.format = VK_FORMAT_R32G32B32_SFLOAT,

.offset = 0}};

return descriptions;

}

Shaded ray

The real reason why I started looking into PVP is that I’ve needed to access vertex and index buffer information from the ray tracing shaders in the heatx demo.

Now I’ve implemented basic textured materials and shadows there, as you can see in the video starting at timestamp 3:20. No more psychedelic coloring with barycentric coordinates.

struct Primitive

{

VertexBuffer vertices;

IndexBuffer indices;

uint material_index;

...

};

layout(buffer_reference, buffer_reference_align = 32) readonly buffer PrimitiveBuffer

{

Primitive v[];

};

layout(push_constant) uniform PushConsts { PrimitiveBuffer primitives; } pc;

If a single level of pointers wasn’t scary enough, we can have pointers to pointers too!

Individual nodes of the scene geometry are stored in the primitives buffer, containing pointers to their vertices and indices. In the ray tracing shaders, we know where a ray intersects with the geometry of the node, but the acceleration structures don’t contain other attributes like UV coordinates. To do that, we need to load the hit triangle from the geometry data:

const Triangle triangle = unpackTriangle(pc.primitives,

gl_InstanceCustomIndexEXT,

gl_PrimitiveID,

attribs);

There are 3 builtin variables that can be used to figure this out:

gl_InstanceCustomIndexEXTis a user controlled value that is specified during building of the acceleration structure.gl_GeometryIndexEXTis the index of a geometry node inside the acceleration structuregl_PrimitiveIDis the index of a triangle in the geometry node

Currently, I don’t have multiple geometries in a single acceleration structure, so gl_GeometryIndexEXT is irrelevant.

In the gl_InstanceCustomIndexEXT, I assigned the indices corresponding to the geometry node location inside the pc.primitives buffer.

With that, we resolved the material and UV coordinates needed for texturing the pixels, and sample the texture as before:

vec3 color =

texture(

sampler2D(textures[nonuniformEXT(m.baseColorTextureIndex)], samplers[0]),

triangle.uv).rgb;

Implementing shadows in a ray tracing pipeline is trivial. In the closest hit shader, the color intensity for the shadowed object is reduced. We assume that the object is in the shadow, and trace a ray from the intersection point to the light position:

shadowed = true;

traceRayEXT(...);

if (shadowed)

{

color *= 0.3;

}

If the ray doesn’t intersect other objects, a miss shader will be invoked that corrects the assumption:

void main() { shadowed = false; }

I’ve added support for alpha masked geometry. This is the geometry where some parts should be rendered as if they don’t exist. An example is the flowers in the Sponza model. They are modeled as rectangles and with alpha masking on the outside, so that the edges outside parts are removed.

This poses a problem for the ray tracing pipeline, as the closest hit shader will be invoked for the geometry that shouldn’t exist. Therefore, any hit shader is added to the pipeline, in which the intersections with alpha masked parts are ignored:

if (m.alphaCutoff != 0.0 && cutoff < m.alphaCutoff)

{

ignoreIntersectionEXT;

}

In these cases, the ray will continue until the next intersection is found or the miss shader is called.

When dealing with alpha masked materials, the geometry inside the acceleration structures shouldn’t be created with VK_GEOMETRY_OPAQUE_BIT_KHR flag.

This also means that gl_RayFlagsOpaqueEXT shouldn’t be passed to traceRayEXT in the ray generation shader, otherwise geometries without the opaque flag will be skipped.

Final words

I think I’ll have to start writing unit tests. It’s becoming a bit hard to verify all features manually. A lot of the interfaces appear to be reasonably stable. I’m considering taking the next step of packaging up the shared code from the demos into a runtime and creating the editor for the engine.

Let’s use GPUs for what they are supposed to do, #returnToGraphics.

For any questions or corrections to this post, leave a comment in discussion thread on GitHub or any other place where you see this.

Diff compared to the state shown in the previous post.

Check out other posts in this series with #niku tag.

tags: C++ - Vulkan - niku - KHR_texture_basisu